The number of tick-borne diseases have more than doubled in the last 13 years, according to a 2018 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Why the increase? Ticks and the diseases they spread are making their way into new regions. Plus, people are traveling more than ever, boosting the odds of bringing an infection home from another country, where more rare vector-borne diseases may be robust. The CDC identifies tick-borne illnesses as a public health threat and admits the problem is widespread and difficult to control. While these diseases occur all over the United States, the Northeast, upper Midwest, and southern parts of the country seem to be particularly vulnerable. While not all tick-related infectious diseases are something to lose sleep over, knowing how to spot the symptoms is crucial to early treatment, which typically involves a round of antibiotics or other prescribed medications. Plus, different types of ticks spread different types of illnesses. Here, the ones you should watch out for, their symptoms, and how to protect yourself from a nasty tick bite this summer.

Lyme disease

What it is: Lyme disease is an infection caused by bacteria that’s transmitted through the bite of an infected blacklegged tick (also known as a deer tick). Symptoms: If left untreated, lyme disease can cause a variety of flu-like symptoms, depending on how long you’ve been infected. This includes fever, chills, headache, fatigue, joint aches, and swollen lymph nodes. Perhaps the most recognizable sign of Lyme is a red bullseye-shaped rash. Symptoms become more severe the longer you go without treatment, leading to shooting pains in your hands and feet, nerve pain, irregular heartbeat, facial palsy, or even inflammation of your brain and spinal cord. How common it is: Lyme disease accounted for 82 percent of all tick-borne diseases reported from 2004 to 2016, the CDC report found, rising from 19,804 cases in 2004 to 36,429 cases in 2016. A total of 402,502 cases have been reported in that span of time. It’s worth noting that these numbers only include reported cases. The CDC estimates that roughly 300,000 Americans are infected with Lyme each year, which is eight to 10 times higher than the number of cases actually reported. While Lyme is most common in the Northeast and upper Midwest, the disease has been making its way to other parts of the country.

Anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis

What it is: Both anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis are infections caused by bacteria that is transmitted through the bite of infected ticks. Anaplasmosis is commonly spread through blacklegged ticks in the Northeast and western blacklegged ticks along the opposite coastline. Ehrlichiosis is spread through the lone star tick and blacklegged ticks. Symptoms: Both diseases exhibit similar symptoms, including fever, headache, muscle pain, malaise, chills, stomach pain, nausea, cough, confusion. Sometimes a rash may occur—identified by splotchy red patches or pinpointed dots—but it is more common in ehrlichiosis (especially in children) than anaplasmosis. A rash is still considered rare in both tick illnesses. How common it is: Anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis are currently the second most common tick-borne diseases affecting Americans, growing from 875 cases in 2004 to 5,750 in 2016. Nearly 40,000 cases total have been reported during that time frame, the CDC says.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever

What it is: Spotted fever rickettsiosis, also known as Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), is a bacterial disease spread through several species of infected ticks, most notably the American dog tick. Symptoms: Early signs of RMSF include fever, headache, nausea and vomiting, stomach pain, muscle pain, and lack of appetite. The most common sign is a rash that usually develops two to four days after infection, the CDC says, which can make RMSF difficult to detect in its earliest stages. The appearance of the rash also varies; some can be red and splotchy, while others look like small dots. RMSF does rapidly progress and can become life-threatening if not treated properly. Because the disease is hard to detect in its earliest stages, the CDC recommends seeing your doctor immediately if you feel sick after being bitten by a tick or hanging out in wooded or high brush areas. How common it is: RMSF grew from 1,713 cases in 2004 to 4,269 cases in 2016, with a total of more than 37,000 reported cases during that time frame. RMSF occurs throughout the U.S., but has most commonly been reported in North Carolina, Tennessee, Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, the CDC says.

Babesiosis

What it is: Babesiosis is caused by microscopic parasites that infect your red blood cells. It’s most commonly transmitted through blacklegged ticks. Symptoms: Babesiosis typically doesn’t present many symptoms. In fact, many infected people may feel fine for a while. If symptoms do pop up, they can start within a week after infection, but usually develop weeks, months, or even longer after you’ve been infected. Common signs include fever, chills, sweats, body aches, nausea, or fatigue. Babesiosis can cause hemolytic anemia, a condition in which your red blood cells are destroyed. It can also be life-threatening in people who are older or have a weak immune system and other serious health conditions, like cancer or kidney disease. How common it is: In 2004, there were no reported cases of babesiosis. That number grew to 1,910 in 2016. While it has steadily trended upwards, reports of babesiosis did slightly decrease between 2015 and 2016. Most cases have occurred in the Northeast and upper Midwest regions.

Tularemia

What it is: Tularemia is caused by a highly infectious bacteria that is transmitted by dog ticks, wood ticks, or lone star ticks. Symptoms: There are several types of tularemia, but two of the most common forms associated with tick bites are ulceroglandular and glandular, according to the CDC. In ulceroglandular tularemia, a skin ulcer—a raw, red, or painful sore—will appear where the bacteria entered your body. This leads to swelling in certain glands, typically in your armpit or groin. Glandular tularemia is similar but does not produce an ulcer. Both forms also cause fever, which can be as high as 104 degrees. How common it is: Tularemia does not occur as frequently as other tick-borne diseases, but it has been on the rise. Only 134 cases were reported in 2004, which grew to 230 in 2016. More than 2,000 cases were reported in that time frame. Tularemia can occur across the U.S., but tends to be more common in central parts of the country, the CDC states.

Powassan virus

What it is: Powassan (POW) virus, which is related to West Nile virus, is transmitted by the bite of an infected tick and cannot be spread directly from person to person. Symptoms: People get sick from one week to a month after infection, but many do not develop any symptoms. Common signs include fever, headache, vomiting, weakness, confusion, loss of coordination, difficulty speaking, and seizures. POW virus is a serious disease and can cause inflammation of the brain or meningitis, which can lead to serious complications. There is currently no specific medicine designed to treat POW virus disease. How common it is: Powassan virus is rare in the U.S. Only one case was reported each year between 2004 and 2006. However, that number jumped to 22 cases in 2016, the highest it has been in 13 years. Most cases have popped up in the Northeast or Great Lakes regions of the U.S.

Heartland virus

What it is: The Heartland virus stems from the Phlebovirus, which can be transmitted by mosquitoes, sandflies, and lone star ticks. The CDC does not know if other types of ticks can transmit this disease. Symptoms: Most patients report signs of the Heartland virus roughly two weeks after the known tick bite. These symptoms are often similar to those of ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis, and include fever, fatigue, decreased appetite, headache, nausea, and muscle or joint pain. While few patients die from the illness, nearly all end up being hospitalized. How common it is: Heartland virus is a rare tick-borne disease, and only 40 cases have been reported in midwestern and southern states since September 2018 to the CDC, notably between May and September.

Tick-borne relapsing fever

What it is: Can you imagine dealing with constant flu-like symptoms? Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) causes a similar scenario, due to a bite of infected “soft ticks,” which differ from the common hard ticks on this list. Soft ticks bite and feed quickly, attaching for less than 30 minutes while causing no pain. They are typically found in rodent burrows, rather than grassy or brushy areas, so humans can fall victim to them while sleeping in rodent-infested cabins, the CDC says. Symptoms: It may take up to a week to develop symptoms of TBRF after a soft tick bite. The signs include a high fever, headache, and muscle or joint pain. The kicker? The symptoms reoccur in a pattern when left untreated, starting with three days of fever, seven days without, three days again, seven without again, and so on. How common it is: While TBRF is rare, it’s not nonexistent, especially in mountainous areas of the U.S., particularly Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, Colorado, and even parts of Texas.

A note on red meat allergy (alpha-gal allergy)

What it is: While not technically classified as a disease, a bite from a lone star tick can cause an allergic reaction to red meat. How? These critters transfer a sugar called alpha-gal into your system, which is found in red meat—like beef, pork, and lamb—but not in humans. Because the sugar travels through your blood, your immune system goes haywire and releases antibodies. Once you try to eat red meat again, your body pumps out histamine in reaction to the sugar, spurring an allergic reaction. Symptoms: If you have the alpha-gal allergy, you will experience symptoms similar to other severe food allergies, like itching, swelling of the throat, lips, and tongue, weakness, nausea, vomiting, headaches, skin rash, and even passing out due to anaphylaxis (difficulty breathing). Unlike typical allergic reactions to food, which tend to be immediate, symptoms may take hours to appear, according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI). How common it is: It’s hard to tell, since meat allergies themselves aren’t very common. However, one preliminary study presented at the 2018 AAAAI and World Allergy Organization Joint Congress found that 40 percent of 222 anaphylaxis cases had a definitive trigger—and the most common was alpha-gal.

How to protect yourself against tick bites

Fear of ticks shouldn’t stop you from enjoying your summer. The CDC says there are few things you can do protect yourself from ticks (as well as mosquitoes and fleas) once outdoor season goes full swing:

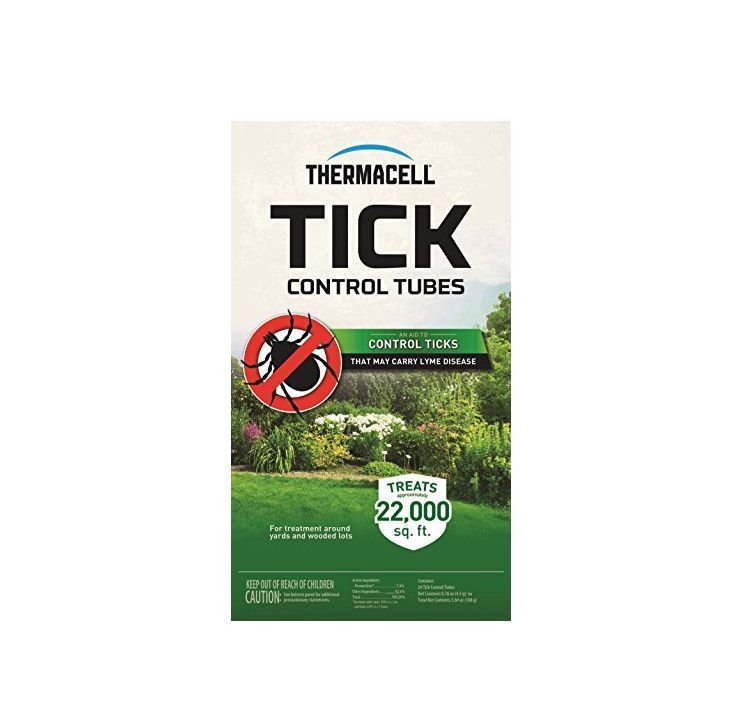

Get rid of ticks from your yard and home by mowing grass frequently, laying down tick control tubes, and treating with insecticide if necessary.Use a tick repellent that contains at least 20 percent DEET, picaridin, or IR3535. Cover up! Opt for long-sleeved shirts and long pants if you will be in wooded or grassy areas.Treat your clothing, gear, and tents with a product that contains at least 0.5 percent permethrin, like this one from Sawyer Premium Permethrin Clothing Insect Repellent.Always do a full body check after you’ve spent time outdoors and shower as soon as you possibly can.Tumble dry your dry clothes on high heat for 10 minutes to kill any ticks you bring inside with you. (If your clothes require washing, use hot water and tumble dry on high for an hour.)Check for and remove ticks from your pets daily.

If you do happen to wind up with a bite (these tick bite pictures can help you identify one), make sure you remove the tick properly with a pair of fine-tipped tweezers. Stay updated on the latest science-backed health, fitness, and nutrition news by signing up for the Prevention.com newsletter here. For added fun, follow us on Instagram.